Support Vector Machines in Hastie et al.

Image from Hastie et al. p. 418

Image from Hastie et al. p. 418

In my effort to blog my way through the rest of my PhD and study for comps, I present to you support vector machines. This is the first of at least 2 and possibly 3 articles on SVMs.

When we covered SVMs in my ML class a couple years ago, we focused on computational methods rather than the math. The focus for comps is more-or-less the opposite so we’re going with chapter 12 of The Elements of Statistical Learning.

I’ve found that many academics in CS seem infatuated with SVMs and I’ve struggled to understand why.

Can anyone explain to me why a great many academic CS folks really really like SVMs?

— Tommy Jones (@thos_jones) February 9, 2020

Thankfully, Twitter was there for me when I needed it most. Apparently, the answer is “kernel methods plus the math is nice”.

A warning for anyone reading this blog post: it’s probably terrible. :) The introduction is probably a good way to think of SVMs. Beyond that, I admit I dive into a lot of detail to help me work through it. But I’m not sure that it’s any more useful than just getting your own copy of The Elements of Statistical Learning.

Introduction

SVMs are one method to make a linear decision boundary for classification. I hear you say “not all decision boundaries are linear”. Well, dear reader, SVMs have an answer for you; read on.

There are two components to SVMs.

- The support vector classifier and

- Kernel methods

The support vector classifier is what creates a linear boundary between classes. (Or it creates a best guess at a linear boundary in the case of overlapping classes.) I describe it in detail below.

Kernel methods are the solution to the fact that not all data are linear. Basically, a “kernel method” is a projection from one space to another. The hope (plan? theory?) is that this new space will lead to a linear separation between classes. In many (most?) cases, the new space will be of higher dimension. This can give us two things: First, as already stated, non-linear can become linear. Second, when classes are overlapping, a higher dimension can give them more separability. In the latter case, this could result in overfitting. However, stick with me, dear reader, and we will see how SVMs address this issue.

The Support Vector Classifier

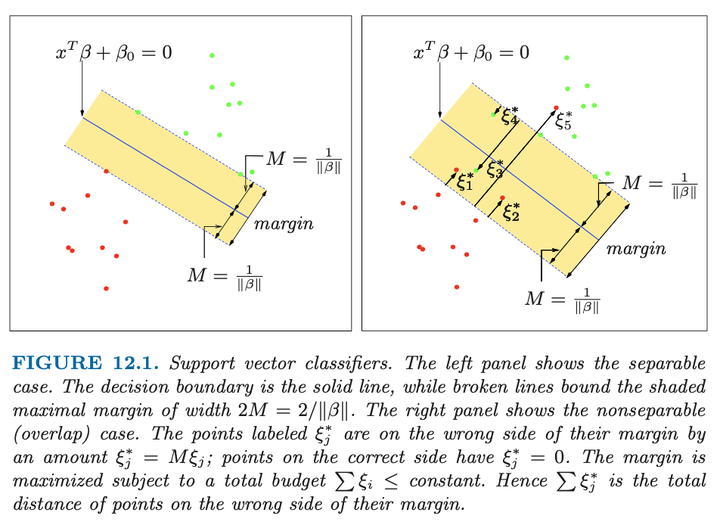

Remember this: The support vector classifier finds the linear hyperplane that separates classes with the maximum margin. The image at the top shows this margin in the case of separable classes (left) and overlapping classes (right).

Some definitions you’ll need to follow the math are:

\[\begin{align} \text{outcomes: } & \{y: y_i \in \{-1,1\}\}\\ \text{features: } & \{x: x_i \in \mathbb{R}^p\}\\ \text{hyperplane: } & \{x: f(x) = x^T\beta + \beta_0\}\\ \text{classification rule: } & G(x) = \text{sign}(x^T\beta + \beta_0)\\ \text{margin: } & M = \frac{1}{\lVert\beta\rVert} \end{align}\]

Note that \(\lVert \beta \rVert = 1\), meaning that \(\beta\) is a unit vector.1

Now we have two optimization problems to consider: In the trivial case, the \(x_i\) are separable by class, \(y_i\). So then it’s just an issue of finding the “right” hyperplane. In the more realistic case, the \(x_i\) are not completely separated by class. This is a more difficult problem and requires a fancier solution.

Separable classes

For the separable case, we have a basic optimization problem:

According to Hastie et al. this can be rephrased and more easily solved by

A total aside that links this back to calculus

You might not be able to solve this analytically, but if I recall my calculus, you’d solve

Where \(s^2\) is a variable introduced to handle inequalities a-la here. And \(\lambda\) is a Lagrange multiplier.

Non-separable classes

When the classes aren’t separable, we have to introduce a new variable, called a “slack variable” \(\xi\). (If—like me—you have trouble pronouncing \(\xi\), it’s pronounced like “sigh”.) \(\xi\) is a vector the same length as \(y\) (and as many rows as \(x\)). Using this variable allows some points to be on the wrong side of the margin. (See the right image, above.)

The standard way to modify the constraint in the face of a slack variable is this:

But we have to more constraints on the total number of misclassified observations. The new constraints are

\[\begin{align} \xi_i \ge 0 \forall i\\ \sum_{i=1}^N \xi_i \leq K \end{align}\]

This leads to the way the support vector classifier is usually defined.

\[\begin{align} \min\lVert\beta\rVert &\text{ subject to } \begin{cases} y_i(x_i^T\beta + \beta_0) \ge 1 - \xi_i \forall i,\\ \xi_ \geq 0, \sum \xi_i \leq K \end{cases} \end{align}\]

Another calculus linking aside

From the link above, if I wanted to do this with calculus I would have the following:

Full disclosure: I’m not 100% sure about the plus sign on \(s_3^2\). Caveat emptor!

Solving it the way Hastie et al. do

Reader, I warn you that this section gets ugly and confusing. Feel free to skip it unless you’re going to build your own support vector classifier from scratch.

Hastie et al. (and I assume the rest of the ML world) rely on a couple of tricks to make the support vector classifier more computationally tractable.

- They restate the problem to something that makes the algebra a little nicer.

- They restate the problem again in a way that makes it nicer to put in a quadratic optimization solver.

To the second, some vocabulary: The “primal” problem is the equation as originally stated. The “dual” problem is an equivalent problem that, if solved, will result in the same answer.

To make it more computationally friendly, the problem above is often re-stated as

The Lagrange (primal) function becomes

I’m inferring that \(\alpha_i\) and \(\mu_i\) are the Lagrange multipliers. But maybe I’m wrong. Caveat emptor again!

Setting the derivatives equal to zero and doing some magic math we see

\[\begin{align} \beta &= \sum_{i=1}^N \alpha_i y_i x_i\\ 0 &= \sum_{i=1}^N \alpha_i y_i \\ \alpha_i &= C - \mu_i, \forall i \end{align}\]

which you can substitute back in to get the dual problem:

The above is subject to several constraints. The first couple are from our problem as we’ve already stated it:

\[\begin{align} &0 \leq \alpha_i \leq C\\ &\text{ and }\\ &\sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_i = 0 \end{align}\]

And the remainder are from the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions. (I’m going to refer to them as the KKT conditions.) The KKT conditions help with finding solutions to nonlinear optimization problems. The additional constraints that they introduce are

\[\begin{align} \alpha_i(y_i(x_i^T\beta + \beta_0) - (1 - \xi_i)) &= 0\\ \mu_i\xi_i &= 0\\ y_i(x_i^T\beta+\beta_0) - (1 - \xi_i) &\geq 0 \end{align}\]

Bringing it home

Ignoring the computational details that we just painfully went through (and still weren’t enough to get you to actually compute it yourself):

The solution for \(\beta\) has the form \(\hat\beta = \sum_{i=1}^N \hat\alpha_i y_i x_x\). For the overwhelming majority of observations, \(i\), \(\hat\alpha_i = 0\). The ones where \(\hat\alpha_i \neq 0\) are due to the case where \((x_i^T\beta + \beta_0) - (1 - \xi_i)) = 0\) exactly. (Note the first and last of the KKT conditions.)

These points are called “support vectors” since \(\hat\beta\) is represented by them alone. Of those, some points lie exactly on the margin. In that case \(\hat\xi_i=0\) and consequently \(0 < \hat\alpha_i < C\). We use these points to solve for \(\beta_0\), usually by averaging across them. For the remainder \(\hat\xi_i>0\) and \(\hat\alpha_i = C\).

Finally, as indicated way up at the top, you need to use the sign of \(x_i^T\hat\beta + \hat\beta_0\) to make a class assignment.

Next time

Next time I’ll write about kernel methods for SVMs and how we use an extension of the support vector classifier to estimate SVMs.

I have two questions about this: 1. Why? 2. Does this include \(\beta_0\)? It’s always seemed more elegant to me when writing linear equations to just do \(x^T\beta\) where one vector of \(x\) is ones. For linear regression, that has no consequences, but it might here (or for ridge or lasso regressions).↩